- Home

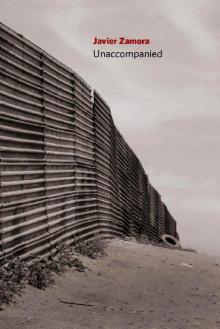

- Javier Zamora

Unaccompanied

Unaccompanied Read online

Note to the Reader

Copper Canyon Press encourages you to calibrate your settings by using the line of characters below, which optimizes the line length and character size:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Pellentesque euismod magna ac diam

Please take the time to adjust the size of the text on your viewer so that the line of characters above appears on one line, if possible.

When this text appears on one line on your device, the resulting settings will most accurately reproduce the layout of the text on the page and the line length intended by the author. Viewing the title at a higher than optimal text size or on a device too small to accommodate the lines in the text will cause the reading experience to be altered considerably; single lines of some poems will be displayed as multiple lines of text. If this occurs, the turn of the line will be marked with a shallow indent.

Thank you. We hope you enjoy these poems.

This e-book edition was created through a special grant provided by the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation. Copper Canyon Press would like to thank Constellation Digital Services for their partnership in making this e-book possible.

para Abuelita Neli y sus hijas

…los que nunca sabe nadie de dónde son… los que fueron cosidos a balazos al cruzar la frontera… los eternos indocumentados…

…the ones no one ever knows where they’re from… the ones burned by bullets when they crossed the border… the eternally undocumented…

Roque Dalton, “Poema de amor” May 14, 1935–May 10, 1975

Contents

Title Page

Note to Reader

To Abuelita Neli

Saguaros

from The Book I Made with a Counselor My First Week of School

Second Attempt Crossing

El Salvador

On a Dirt Road outside Oaxaca

Cassette Tape

To President-Elect

Pump Water from the Well

Instructions for My Funeral

Montage with Mangoes, Volcano, and Flooded Streets

The Pier of La Herradura

Dancing in Buses

How to Enlist

Documentary

ARENA

“Don Chepe”

Disappeared

Rooftop

This Was the Field

Politics

Aftermath

For Israel and María de los Ángeles

Crybaby

Abuelita Neli’s Garden with Parakeets Named Chepito

I Don’t Want to Speak of “Don Chepe”

How I Learned to Walk

Postpartum

“Ponele Queso Bicho” Means Put Cheese on It Kid

Then, It Was So

Mom Responds to Her Shaming

Alterations

Aubade

Prayer

Abuelita Says Goodbye

Let Me Try Again

Citizenship

San Francisco Bay and “Mt. Tam”

Doctor’s Office First Week in This Country

Vows

Nocturne

Deportation Letter

Seeing Your Mother Again

Exiliados

June 10, 1999

About the Author

Also by Javier Zamora

Acknowledgments

Copyright

Special Thanks

To Abuelita Neli

This is my 14th time pressing roses in fake passports

for each year I haven’t climbed marañón trees. I’m sorry

I’ve lied about where I was born. Today, this country

chose its first black president. Maybe he changes things.

I’ve told Mom I don’t want to have to choose to get married.

You understand. Abuelita, I can’t go back and return.

There’s no path to papers. I’ve got nothing left but dreams

where I’m: the parakeet nest on the flor de fuego,

the paper boats we made when streets flooded,

or toys I buried by the foxtail ferns. ¿Do you know

the ferns I mean? The ones we planted the first birthday

without my parents. I’ll never be a citizen. I’ll never

scrub clothes with pumice stones over the big cement tub

under the almond trees. Last time you called, you said

my old friends think that now I’m from some town

between this bay and our estero. And that I’m a coconut:

brown on the outside, white inside. Abuelita, please

forgive me, but tell them they don’t know shit.

Saguaros

It was dusk for kilometers and bats in the lavender sky,

like spiders when a fly is caught, began to appear.

And there, not the promised land but barbwire and barbwire

with nothing growing under it. I tried to fly that dusk

after a bat said la sangre del saguaro nos seduce. Sometimes

I wake and my throat is dry, so I drive to botanical gardens

to search for red fruits at the top of saguaros, the ones

at dusk I threw rocks at for the sake of hunger.

But I never find them here. These bats speak English only.

Sometimes in my car, that viscous red syrup

clings to my throat and I have to pull over —

I also scraped needles first, then carved

those tall torsos for water, then spotlights drove me

and thirty others dashing into paloverdes;

green-striped trucks surrounded us and our empty bottles

rattled. When the trucks left, a cold cell swallowed us.

from The Book I Made with a Counselor My First Week of School

His grandma made the best pupusas, the counselor wrote next to

Stick-Figure Abuelita

(I’d colored her puffy hair black with a pen).

Earlier, Dad in his truck: “always look gringos in the eyes.”

Mom: “never tell them everything, but smile, always smile.”

A handful of times I’ve opened the book to see running past cacti

from helicopters, running inside detention cells.

Next to what might be yucca plants or a dried creek:

Javier saw a dead coyote animal, which stank and had flies over it.

I keep this book in an old shoebox underneath the bed. She asked in Spanish,

I just smiled, didn’t tell her, no animal, I knew that man.

Second Attempt Crossing

for Chino

In the middle of that desert that didn’t look like sand

and sand only,

in the middle of those acacias, whiptails, and coyotes, someone yelled

“¡La Migra!” and everyone ran.

In that dried creek where forty of us slept, we turned to each other,

and you flew from my side in the dirt.

Black-throated sparrows and dawn

hitting the tops of mesquites.

Against the herd of legs,

you sprinted back toward me,

I jumped on your shoulders,

and we ran from the white trucks, then their guns.

I said, “freeze Chino, ¡pará por favor!”

So I wouldn’t touch their legs that kicked you,

you pushed me under your chest,

and I’ve never thanked you.

Beautiful Chino —

the only name I know to call you by —

farewell your tattooed chest: the M,

the S, the 13. Farewell

the phone number you gave me

when you went east to Virginia,

and I went west to San Francisco.

You called

twice a month,

then your cousin said the gang you ran from

in San Salvador

found you in Alexandria. Farewell

your brown arms that shielded me then,

that shield me now, from La Migra.

El Salvador

Salvador, if I return on a summer day, so humid my thumb

will clean your beard of salt, and if I touch your volcanic face,

kiss your pumice breath, please don’t let cops say: he’s gangster.

Don’t let gangsters say: he’s wrong barrio. Your barrios

stain you with pollen. Every day cops and gangsters pick at you

with their metallic beaks, and presidents, guilty.

Dad swears he’ll never return, Mom wants to see her mom,

and in the news: black bags, more and more of us leave.

Parents say: don’t go; you have tattoos. It’s the law; you don’t know

what law means there. ¿But what do they know? We don’t

have greencards. Grandparents say: nothing happens here.

Cousin says: here, it’s worse. Don’t come, you could be…

Stupid Salvador, you see our black bags, our empty homes,

our fear to say: the war has never stopped, and still you lie

and say: I’m fine, I’m fine, but if I don’t brush Abuelita’s hair,

wash her pots and pans, I cry. Tonight, how I wish

you made it easier to love you, Salvador. Make it easier

to never have to risk our lives.

On a Dirt Road outside Oaxaca

The Mexican never said how long.

¿How long? Not long. ¿How much?

Not much. Never told us we’d hide in vans like matchsticks.

In our town, we’d never known Mexicans

besides the women and men in soap operas,

so in our heads, we played the fence,

the San Ysidro McDonald’s, a quick run, a van.

Not long, not long at all. In Oaxaca,

a small brown lizard licks horchata from my hand —

we’re friends, we pick names for each other.

Hola Paula. Hola Javier, she says.

We play the fence, a quick run, the van…

¿How long? Not long. On the dirt,

our knees tell truths to the cops’ front-sights and barrels.

¿How much? Not much.

We’d never known Mexicans besides Chente,

Chavela Vargas. We’re on the dirt

like dogs showing nipples

to offspring, it’s not spring,

and we’re going to where there is spring,

we say it’s gonna be alright,

it’s gonna be just fine —

my hands play with Paula.

Cassette Tape

A

To cross México we’re packed in boats

twenty aboard, eighteen hours straight to Oaxaca.

Vomit and gasoline keep us up. At 5 a.m.

we get to shore, we run to the trucks, cops

rob us down the road — without handcuffs,

our guide gets in their Ford and we know

it’s all been planned. Not one peso left

so we get desperate — Diosito, forgive us

for hiding in trailers. We sleep in Nogales till

our third try when finally I meet Papá Javi.

»

Mamá, you left me. Papá, you left me.

Abuelos, I left you. Tías, I left you.

Cousins, I’m here. Cousins, I left you.

Tías, welcome. Abuelos, we’ll be back soon.

Mamá, let’s return. Papá ¿por qué?

Mamá, marry for papers. Papá, marry for papers.

Tías, abuelos, cousins, be careful.

I won’t marry for papers. I might marry for papers.

I won’t be back soon. I can’t vote anywhere,

I will etch visas on toilet paper and throw them from a lighthouse.

«

When I saw the coyote —

I didn’t want to go

but parents had already paid.

I want to pour their sweat,

each step they took,

and braid a rope.

I want that cord

to swing us back to our terracota roof.

No, I wanted to sleep

in my parents’ apartment.

B

You don’t need more than food,

a roof, and clothes on your back.

I’d add Mom’s warmth, the need

for war to stop. Too many dead

cops, too many tattooed dead.

¿Does my country need more of us

to flee with nothing but a bag?

Corrupt cops shoot “gangsters”

from armored cars. Javiercito,

parents say, we’ll send for you soon.

»

Last night, Mom wanted to listen to “Lulu’s Mother,”

a song she plays for the baby she babysits.

I don’t know why this song gets to me, she said, then:

“Ahhhh Lu-lu-lu-lu / don’t you cry / Mom-ma won’t go / a-way /

Ahhhh Lu-lu-lu-lu / don’t you cry / Pop-pa won’t go / a-way…”

It’s mostly other nannies in the class; it’s supposed to help

with the babies’ speech development, she says, mijo,

sorry for leaving. I wish I could’ve taken you to music classes.

She reached over, crying. Mom, you can sing to me now,

was all I could say, you can sing to me now.

To President-Elect

There’s no fence, there’s a tunnel, there’s a hole in the wall, yes, you think right now ¿no one’s running? Then who is it that sweats and shits their shit there for the cactus. We craved water; our piss turned the brightest yellow — I am not the only nine-year-old who has slipped my backpack under the ranchers’ fences. I’m still in that van that picked us up from “Devil’s Highway.” The white van honked three times, honks heard by German shepherds, helicopters, Migra trucks. I don’t know where the drybacks are who ran with dogs chasing after them. Correction: I do know. At night, they return to say sobreviviste bicho, sobreviviste carnal. Yes, we over-lived.

Pump Water from the Well

This is no shatter and stone.

Come skip toes in my chest, Salvador.

I’m done been the shortest shore.

¿And did you love all the self out of you for me?

I want you to torch the thatch above my head.

To be estero. To be mangroves.

There are mornings I wake with taste of tortillas in warmed-up milk.

There are pomegranates no one listens to.

¿Is this the mierda you imagined for me?

Everywhere is war.

The patch of dirt I pumped water from to bathe.

Chickens, dogs, parakeets, this was my block.

The one I want to shut off with rain.

Where I want to plant an island.

Barrio Guadalupe hijueputa born and bred cerote ¿qué onda?

The most beautiful part of my barrio was stillness

and a rustling of wings caught in the soil calling me to repair it.

Don’t tell me I didn’t bring the estero up north where there’s none.

I’ve walked uptown. I saw Mrs. Gringa.

The riff between my fingers went down in whirlpools.

Silence stills me. Pensé quedarme aquí I said.

I don’t understand she said. From my forehead,

the jaw of a burro, hit on the side and scraped by a lighter to wake the song

that speaks two worlds.

The kind of terrifying current.

The kind of ruinous wind.

Instructions for My Funeral

Don’t burn me in no steel furnace, burn me

in Abuelita’s garden. Wrap me in blue-

white-and-blue [ a la mierda patriotismo ].

Douse me in the cheapest gin. Whatever you do,

don’t judge my home. Cut my bones

with a machete till I’m finest dust

[ wrap my pito in panties so I dream of pisar ].

Please, no priests, no crosses, no flowers.

Steal a flask and stash me inside. Blast music,

dress to impress. Please be drunk

[ miss work y pisen otra vez ].

Bust out the drums the army strums.

Bust out the guitars guerrilleros strummed

Unaccompanied

Unaccompanied